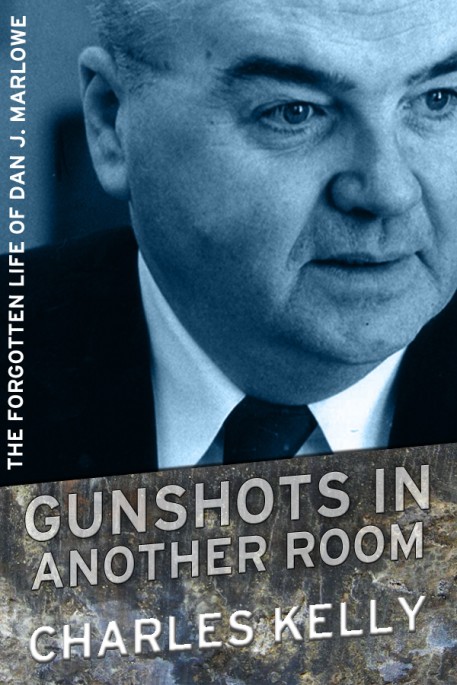

This is my most recent book, GUNSHOTS IN ANOTHER ROOM: THE FORGOTTEN LIFE OF DAN J. MARLOWE. The biography interweaves the stories of the lives of Dan Marlowe, who was a top paperback suspense novelist for Fawcett Gold Medal, and Al Nussbaum, a bank robber who J. Edgar Hoover once called “the most cunning fugitive in the country.” Marlowe and Nussbaum became friends and fellow mystery writers, so close that Nussbaum invited Marlowe to live with him in Los Angeles after Marlowe was stricken by amnesia at the age of 62. The book is a combination author bi0 and true-crime epic, encompassing the careers of Nussbaum and his bank-robbing partner Bobby Wilcoxson, who was alternately nicknamed “One-Eye” and “Bad Eye” because he’d lost an eye in an accident. Veteran mystery writer Bill Crider has lauded this bio. “It’s well-written and it’s a fascinating story,” Crider said on his Pop Culture Magazine blog. “Highly recommended.” It’s for sale as a trade paperback on Amazon for $19.95 and as an ebook for $4.99. To buy it, just click on the title above. It’s also available on Barnes and Noble, iBooks and Kobo.

GRACE HUMISTON AND THE VANISHING, a novel about the adventures of Grace Humiston, a crime-solving lawyer, is now available on Amazon. Though the story is heavily fictionalized, Humiston was real. The story has a basis in life: Humiston actually did solve the disappearance of high school student Ruth Cruger in 1917 in New York City. And the case did generate wild headlines about murder and white slavery. This novel was a finalist for the 2012 Amazon Breakthrough Novel Award and was praised by bestselling thriller author Linda Fairstein and top literary agent Donald Maass.

For the factual background of the case, see my “ebook” (actually a 12-page article), also available on Amazon and called THE CRIME LAWYER: THE TRUTH ABOUT GRACE HUMISTON.

available on Amazon and called THE CRIME LAWYER: THE TRUTH ABOUT GRACE HUMISTON.

FINNEGAN’S WAY: THE SECRET POWER OF DOING THINGS BADLY is a self-help book that tells the tale of a mysterious man named Finnegan who is brimming with advice about how to make the most out of life by doing things poorly. It’s humorous, but makes a serious point: to succeed at anything, you have to be brave enough to risk failure. In fact, you have to embrace failure. This fable is available as an ebook on Amazon.

FINNEGAN’S WAY: THE SECRET POWER OF DOING THINGS BADLY is a self-help book that tells the tale of a mysterious man named Finnegan who is brimming with advice about how to make the most out of life by doing things poorly. It’s humorous, but makes a serious point: to succeed at anything, you have to be brave enough to risk failure. In fact, you have to embrace failure. This fable is available as an ebook on Amazon.

My short story, “The Eighth Deadly Sin,” was published in the collection PHOENIX NOIR, issued by Akashic Books.

Now let’s take a look a three books I didn’t write. These are hardboiled classics written by Dan J. Marlowe. I did write the introductions for the ebook versions being sold on Amazon and Smashwords.

Marlowe’s best book, in which he created the amoral bank robber character who would become known as Earl Drake, was THE NAME OF THE GAME IS DEATH, issued in 1962.

Marlowe’s book THE VENGEANCE MAN, a 1966 brute-force novel, has been re-issued with the more clipped title VENGEANCE MAN.

ONE ENDLESS HOUR, the sequel to THE NAME OF THE GAME IS DEATH, was published in 1969. Marlowe wrote the book, so the story goes, at the insistence of his friend, the bank robber Al Nussbaum.

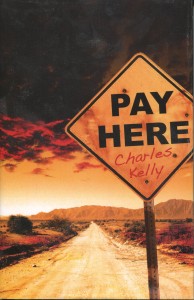

PAY HERE, my first novel, was published by Point Blank Press. It’s available on Amazon as a hardback, paperback or ebook. The story is a version of “The Third Man” set in the modern  desert Southwest. Michael Callan, a reporter for the Phoenix Scribe who grew up in Ireland and was homeless as a boy, has just been to the funeral of his ex-girlfriend. He’d like to forget her because she wasn’t good for him, and not much good for anybody else. But that’s not going to happen. Callan narrates. He starts with a young woman in Omaha who thinks she’s just gotten some good news, but hasn’t. Here’s the first chapter.

desert Southwest. Michael Callan, a reporter for the Phoenix Scribe who grew up in Ireland and was homeless as a boy, has just been to the funeral of his ex-girlfriend. He’d like to forget her because she wasn’t good for him, and not much good for anybody else. But that’s not going to happen. Callan narrates. He starts with a young woman in Omaha who thinks she’s just gotten some good news, but hasn’t. Here’s the first chapter.

CHAPTER ONE

Daly Marcus thought the voice on the phone was offering her a new life, but she got it wrong. A male voice—smooth on the surface, pebbled with a rattling tone—saying Rhea Montero wanted her in Arizona. One of Rhea’s businesses needed someone like Daly, someone artistic who could produce beautiful items for public sale. Rhea had arranged an airline ticket. Would Daly come right away?

Daly’s heart jumped at the thought of doing something for Rhea after all Rhea had done for her. Of course she would come “right away.” But the caller didn’t foresee how she’d interpret that term. He’d never dealt with artists, except those who performed with their clothes off, and he knew little about Daly. He didn’t know she’d gone without a vacation for a long time, or that she lived frugally in a converted warehouse in downtown Omaha, or that she’d been waitressing as she tried to start a business handcrafting porcelain angels. He didn’t know her income left no extra money to buy a gift for an old friend. So he assumed Daly would use the airline ticket, booked for a flight the following day. That assumption cost him his life.

No one eagerly chooses to ride a long-distance bus in the United States. The drivers are sullen, your fellow passengers questionable, the rest breaks infrequent and short. But Daly rode a bus from Omaha to Phoenix at the hottest time of the summer and considered it an adventure. That was Daly. At 30, she was still inviting beggars home for coffee, accepting phone pitches, petting vicious dogs and choosing to see the best in male companions who explained things to her with their fists.

At the last moment, without bothering to phone Rhea, she had cashed in the $212 one-way airline ticket. With the $134 difference between that and her bus ticket, she bought an embroidered caftan for Rhea as an arrival gift. A journey that would have taken her two hours by air—and put her into Phoenix at a time and place known to Rhea—was replaced by one that took her a day and a half.

It was a good trip. Daly enjoyed herself immensely and met people. In particular, she met Shihara, a stunning six-foot black woman from the Twin Cities who had once been a chorus dancer in Las Vegas. Shihara, hard as a Kentucky pine despite her 50 years, was making her way leisurely through the central and southwestern United States on a serial visit to relatives that would end with a two-week stay in Phoenix with her eldest daughter, who worked for the phone company. Shihara talked of mob guys, of gambling runs that hadn’t lasted long enough. She spoke of her hell-raising days.

“You goin’ down to meet a man?” Shihara asked, fanning herself with a feather boa as the flatlands of Oklahoma drifted by outside, the tan hardpan painted green by the tinted bus windows.

“No,” said Daly. “An old friend, sort of like a sister.” She smiled. “I’d do anything for her.”

Old thoughts went around in Shihara’s eyes. Her head rode high before her eyelids dropped and the look of memory got darker. Shihara bit her lip and looked away.

“Anything’s a lot to do for someone,” she muttered. “Be careful, little child. Hope she don’t ask.”

From a pay phone inside the bus station in Phoenix, Daly called Rhea’s number. She had declined Shihara’s offer of a ride—the older woman’s daughter had picked her up in a Dodge Neon—but had accepted parting gifts of a much- thumbed magazine and an extra feather boa. Now Daly swished her boa at the air-conditioned air, listened to the buzzing phone at the other end of the line, and looked about at the tangled humanity passing in and out of the station. The place was new and bunker-like and inconvenient. Though Daly didn’t know it, it had been moved from downtown to make way for a parking garage so people with money to spend could more easily patronize the new ballpark and America West Arena.

The move also made provision for people without money—the dark, rumpled people Daly saw around her. They had been banished to this terminal tucked away near the airport, in a wasteland of rumbling freeways, vacant lots rolling with hot dust, municipal facilities walled in by stone redoubts topped with barbed wire. Daly could see the bus station operators expected many immigrant travelers, because the signs were in both English and Spanish. “Lockers and Video Games” was rendered as Armarios & Videos, “Smoking Patio” as Plaza de Fumar, “Restrooms” as Baños. Among the postings she also noted the universal command for the victims of this earth: Pague Aqui. Pay Here.

Daly blended comfortably with the short-money assemblage, and accepted the difficulty of getting through on the phone. She was traveling light—carrying a green canvas duffel bag stuffed with clothes, a bath kit, the gift caftan for Rhea, a scuffed paperback copy of Siddhartha—and she could easily hole up for a few hours in the station, sipping Cokes and reading the copy of Ebony that Shihara had given her, periodically calling Rhea’s number. You couldn’t be too particular if you wanted to be free.

But after the ninth or tenth ring, just as Daly was prepared to give up, the phone was snatched up and a man’s voice cut at her.

“Yeah?” he said. “Who’s this?”

Daly, who was a close listener despite her casual attitude, immediately noted that this voice was not that of the man who had invited her to Phoenix. The voice of that man had been smooth, at least superficially. There was nothing smooth about this man’s voice, only the hoarse accents she associated with too much smoke and whiskey. Voices like that were always ready to fight and hurt. Best be soothing, then.

She excused herself, though there was no reason to do so, and asked, “Is Rhea Montero there?”

No response, not immediately. But Daly sensed a kind of response. Sometimes it’s possible to hear something in silence, especially at the other end of a phone line. That was what Daly heard—hesitation, suspicion—as the man declined to answer for the longest time. Daly couldn’t help herself, her stomach got tight. Maybe she was to blame for the problem, maybe her question had been at fault. Maybe she had misled him in some way, made him think she was a telephone solicitor, an upset customer, a vendor with an unpaid bill.

Finally, he spoke.

“No. Not here.”

And Daly released the breath she had been holding.

Though the words were simple enough, the man’s attitude was disturbing. Who was he, exactly? Daly had no idea specifically what Rhea did, what kinds of people she employed. Out of the blue, Rhea had tracked her to Omaha the year before, had sent her a brief, searching letter asking about Daly’s current situation. Was she working? Married? Involved with anyone? Rhea—except for explaining that she had now changed her name and was setting up “an enterprise” in the Southwest, was vague about her own life. From the few clues in her message, Daly concluded Rhea was dealing in artifacts or replicas—valuable items that moved out of Latin America and into the United States, to be distributed by Rhea’s vast marketing network (In a way, of course, that was true). But people who handled that sort of business, Daly thought, would be accommodating and friendly. Not like this sharp-voiced man.

Daly resolved to be patient.

“I was hoping— ” she said, then paused. This man did not care what she was hoping, and it was unfair to burden him with that knowledge. Of course, he wanted to know who she was, to assure himself she was legitimate. “Please,” she said. “I’m a friend of Rhea’s.”

Instead of calming him, this assertion seemed to prod the man’s distrust.

“You are, huh?” he said. “If you’re such a friend, why are you calling me to ask this shit? You should know by now.”

Daly believed people can be changed through understanding, that each of us craves to communicate, no one is sincerely hateful. This was central to her character, key to the way she operated. She believed that if one spoke gently to people, they would come around.

“I’ve been on a bus for two days,” Daly said, trying to keep the weariness out of her voice. “I know I should have called ahead and warned somebody, but I didn’t. I don’t know why not, I guess I just didn’t think. Now I’m at the Greyhound Bus station in Phoenix, it’s on Buckeye Road, and I need a ride. Please tell me when Rhea will be coming back.”

This time, the reply was immediate.

“She won’t be coming back.”

The statement clattered with menace, and a burning spot of pain sprang in Daly’s forehead. It occurred to her that the man wouldn’t be so mean if he knew that he would have to answer to Rhea later, if Rhea knew he had been rude to a friend, almost a sister. Daly certainly was not seeking retribution; she didn’t want anyone dressed down. It was just that the man’s attitude worried her. And she couldn’t make sense of his cryptic response.

“You mean she’s left town?”

“Town and everything else.”

Daly sensed a subtle change in his tone—a lessening of his uneasiness. Perhaps he was finally recalling that Rhea, indeed, was expecting a visitor, that Daly fit into some scenario he had forgotten. Or perhaps he had simply decided it didn’t really matter what he told her. After all, the situation was there for all to see.

“Rhea got killed in a wreck yesterday,” he said, seeming to relish the information. “On I-10, down toward Casa Grande.” He paused as an actor does, ensuring his best lines will have impact. “Went under a semi, took the top of the car right off. Killed just like that, never knew what hit her. I always told her she was nuts to let that crazy bastard drive, shitty doctor and a worse driver, but she’d never listen to me.”

Now the formerly tight-lipped man couldn’t stop talking. He went on and on, providing details, gossiping along without a care, as Daly’s world fell away, the shuffle of people around her fading into the background, the hard plastic phone melting into her hand, her thoughts hissing like far-off surf. She wasn’t prepared for this, and how could she be? No-one ever is. Devastation is always unexpected. We must believe things will be fine, events will be predictable, circumstances will not change. Often, we don’t realize how much we live in the future, happy in prospect, laughing with friends, feeling old hurts recede, being with those we love, or think we do. Daly had been living like that—close with Rhea, no longer alone.

“Funeral’s in an hour,” the man was saying. “You want directions?”

Now she was shocked and cold. She didn’t want to face the situation, but she had a duty, and Daly took duty seriously. Yes, she said, give me directions, though she had just lost the one direction she had in life. Despite her artistic temperament, Daly Marcus had fixed goals: build up the angels business, find a man to share her life (“a good man”—she could be old-fashioned), re-establish her sisterly relationship with Rhea. The search for a man had been going badly, the angels business sputtering. And now. . . Daly could hear her voice asking for details, hear her brain click, recording them. She could feel her hand replacing the phone, hear her feet moving slap-slap on the smooth composition-stone floor toward the ticket counter, her voice speaking again, with no feeling in it.

A shuttle was leaving for Tucson in twenty minutes and it had a seat open. Yes, it would take her where she needed to go. It would travel south on the Interstate, not far from the graveyard. Could she be dropped there? Well, that was quite unusual, it was not a scheduled stop. But the company always tried to accommodate. That was why it had a reputation for service. Fine. She would take advantage of the company’s desire to serve. She would get the driver to let her off. She would say goodbye to Rhea. And that would be the end of the brightness, her world shoveled under a patch of desert, her future suffocated, the one good person in her past ripped away from her forever.

If things had only been that simple. So much trouble would have been averted, so many deaths avoided, so much terrible knowledge left unknown. There would have been no need to tell the kind of bloody tale Mexican journalists call La Nota Roja, The Red Story. How much better things would have been for Daly Marcus. And for me.